Neural layer for Governance: AI between DPI and legacy systems

Indians, and the world, have been in awe after the implementation of UPI - a real-time payment system that allows instant money transfers between bank accounts using a mobile application. It uses a unique identifier, the UPI ID or Virtual Payment Address (VPA), to facilitate transactions.

But in a way, it is a layer. What was it built on?

It was built on the Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) Infrastructure. Infact, the IMPS was built on the National Financial Switch (NFS) - an interoperable network connecting ATMs enabling inter-banking transactions. NFS routes transactional information between banks when an ATM is used. It operates as a central platform for fund withdrawals, deposits, and other services.

Along-with UPI (payments), India has built multiple foundational pillars of Digital Public Infrastructure like verifiable identity and registries, data sharing, credentials, and open models, signatures and consent, discovery and fulfilment networks.

While these pillars have revolutionized citizen-facing services, they rest upon government backend systems that often remain trapped in legacy architectures. It is similar to building a modern smart city on old plumbing - the new facade is impressive, but the foundation needs reinforcement.

The Government does not run on DPI, it runs on a mountain of legacy technology systems built and modified over years. Take the example of EPFO (Employees' Provident Fund Organization) platform - it manages provident fund accounts, pension disbursements, and employee services for millions of workers. It has been running since around 15 years is filled with accumulated technical debt over time. There are multiple such examples like:

VAHAN (for vehicle registration) and Sarathi (for driving licenses) are nationwide systems deployed by the National Informatics Centre (NIC) to automate Regional Transport Offices (RTOs).

ICEGATE (Indian Customs Electronic Gateway), launched in 2002, is the backbone for customs clearance, trade documentation, and tax compliance for importers and exporters.

The MCA21 portal, introduced in 2006, digitizes company registration, compliance filings, and public record access.

Indian Railways’ reservation and ticketing system (IRCTC)

DGFT’s online portal facilitates export-import licensing, trade documentation, and policy compliance.

The Election Commission’s Electoral Roll Management System (ERMS) and Voter Services Portal manage voter registration and election logistics.

India Post’s core banking system (for postal savings accounts) and parcel tracking services.

Applications for horizontal functions like procurement, human resources management, public finance, files, public grievances, etc.

These systems are the backbone of the digital government architecture handling case processing, record-keeping, inter-departmental workflows, decision support and so much! Many of them evolved in silos, built on different platforms and databases over decades.

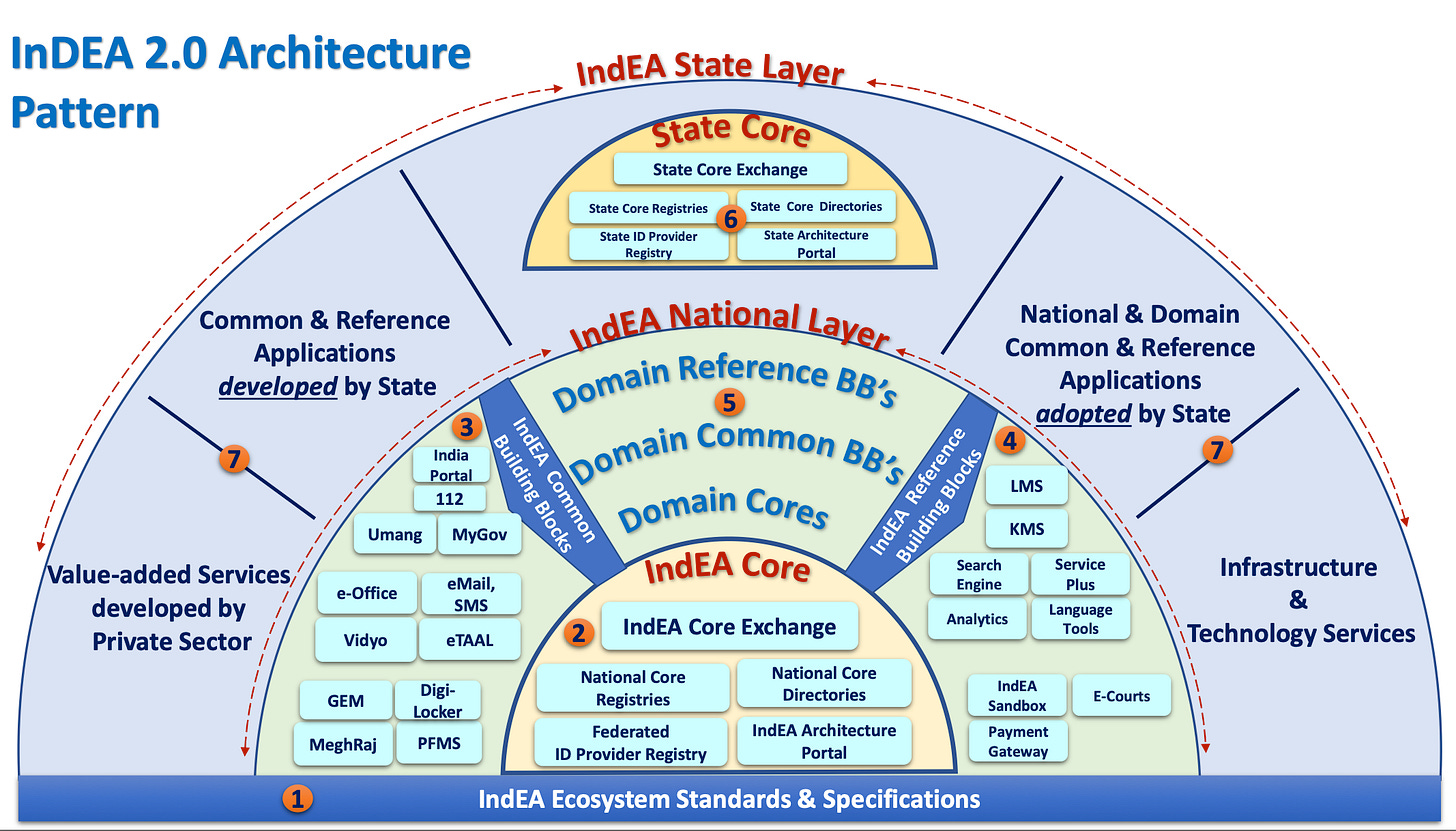

To address this, India has formulated the India Enterprise Architecture (IndEA) framework. IndEA is a holistic architecture blueprint for e-governance that aims to bring “One Government” experience by unifying disparate systems under common standards. It provides a set of reference models across eight domains – Business, Data, Application, Technology, Integration, Security, Performance, and Governance – to guide how government IT systems should be designed and interoperate.

We will not deep dive into this. In short, IndEA provides the blueprint to modernize and integrate India’s government backend, transforming a collection of siloed legacy systems into a cohesive digital government.

Why does this matter?

This creates a fertile ground for AI to be layered on top as a powerful enabler.

AI as a horizontal layer sandwiched between DPI and backend systems:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can serve as a horizontal layer that ties the two together – enhancing interoperability, automating processes, and improving efficiency across the board. AI’s role here is to intelligently connect citizen-facing services with the behind-the-scenes machinery of government.

There are several dimensions to this integration:

Interoperability and Data Integration: One challenge in government technology is that different systems speak different “languages” in terms of data formats and protocols. AI can help bridge these gaps by using techniques like natural language processing and data mapping to translate or mediate between systems.

Can it help map various triggers and services across a citizen’s lifecycle?

AI can also assist in entity resolution (figuring out that records in different databases refer to the same person or entity) using machine learning on identifiers, which improves interoperability of legacy silos.

Can it help map beneficiaries who receive ESIC and PMJAY insurance and help rationalize these programs?

In essence, AI can act as the “glue” that makes the DPI’s one-stop interfaces communicate with many departmental systems behind the scenes.

Automation of Routine Processes: Many government workflows involve repetitive, rules-based tasks – checking forms for completeness, routing applications to the right office, generating acknowledgments, etc. AI-driven automation can handle a lot of this mundane workload. Machine learning models and robotic process automation (RPA) bots can be trained to perform tasks like triaging incoming requests or emails, data entry, and verification of documents. For instance, an AI system could read and classify public grievances on CPGRAMS platform or emails and forward them to the appropriate department automatically, reducing manual sorting. In internal processes, AI could assist with files in eOffice by recommending laws and regulations while drafting policy proposals. It could free up officials to focus on more complex tasks that require judgment.

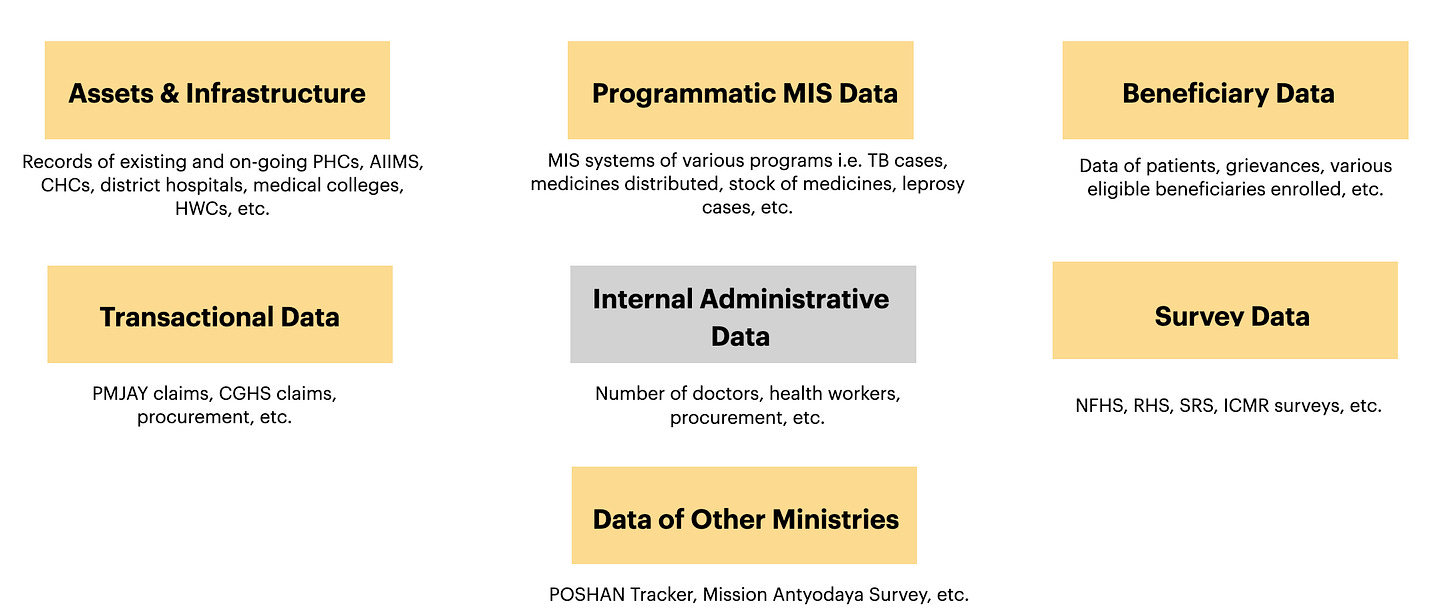

Enhanced Decision Support and Analytics: Government systems accumulate vast amounts of data (from DPI transactions, service usage patterns, policy outcomes, etc.). AI can analyze these data flows to provide insights for decision-making and to optimize processes. For example, AI algorithms can detect patterns in healthcare or welfare data to identify fraudulent activities or to flag cases that need intervention. In a DPI-enabled service (say, an online scholarship application), an AI model could cross-verify the applicant’s details against multiple databases (education records, income data, etc.) and score the application for eligibility, assisting officers in making faster and data-driven decisions. Predictive analytics can forecast service demand (e.g., predicting regions that might need more ration supplies or doctors based on trend data), allowing proactive resource allocation. Essentially, AI serves as an analytical bridge, turning raw data from both citizen interactions and internal systems into actionable intelligence for policy and operations.

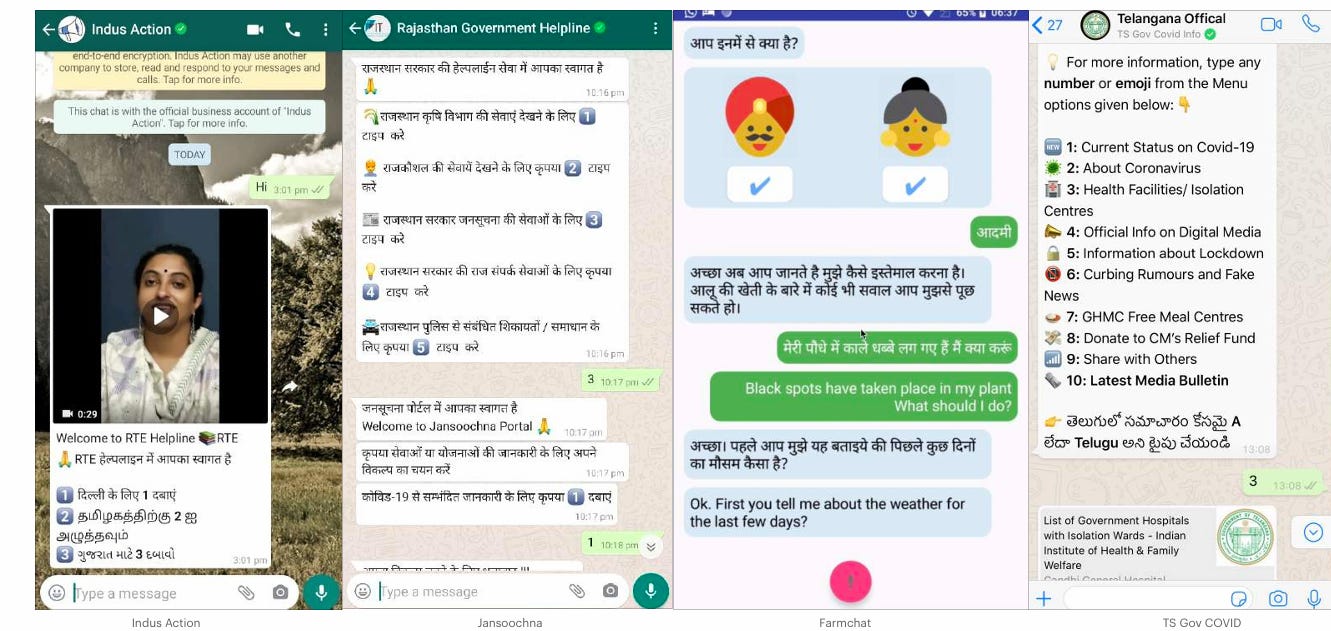

Unified Citizen Experience through AI: Perhaps the most visible way AI bridges front and back is by creating a unified interface for citizens. One can imagine AI-powered virtual assistants or chatbots that sit on top of DPI platforms to help users navigate services. These AI assistants can interface with multiple backend systems on the user’s behalf. A citizen could ask a single chatbot, “What is the status of my income tax refund and my passport renewal?” – the AI assistant can authenticate the user (via DPI’s identity layer), fetch data from the tax system and the passport system, and respond with answers, all in one conversation. Such an AI layer effectively hides, and it does not solve the complexity of multiple departments.

This not only improves user experience (making government “faceless” and seamless) but also forces interoperability on the backend – since the AI must pull information from various sources, those sources must be integrated. AI-driven voice bots in local languages could further make services accessible to those who are less tech-savvy, fulfilling the inclusion mandate.

Workflow and Resource Management: AI can optimize how backend processes execute by dynamically routing work and resources. For example, in a city administration, an AI system analyzing civic issue reports from a DPI app could prioritize them based on severity and location, then automatically assign tasks to the nearest field workers, creating a more efficient resolution mechanism. In government call centers or helpdesks, AI can assist human agents by fetching relevant case history from backend systems in real-time, or even handle straightforward queries entirely through voice AI. By sitting horizontally across systems, AI observes the end-to-end workflow and can identify bottlenecks – perhaps noticing that certain types of applications always get stuck in a particular office – and suggest process changes. This kind of process intelligence helps continually streamline service delivery.

Other use cases of AI where DPI is not really involved:

Citizen Engagement:

AI can improve citizen engagement in India by creating a feedback loop from informing citizens about laws and policies to gathering insights on public sentiment. Advanced analytics and natural language processing can make open data platforms more accessible, automatically translating and summarizing complex information so that citizens understand their rights, the workings of government, and proposed legislation.

Real-time analysis of polls, surveys, and social media chatter could provide policymakers with nuanced perspectives on emerging issues, enabling them to refine initiatives on the fly. Finally, by aggregating feedback from diverse channels such as helplines, community forums, and digital platforms - AI can identify service gaps, prioritize grievances, and deliver timely insights to decision-makers, ensuring that each stage of engagement culminates in more responsive and inclusive governance.

Writing, interpreting and reforming Legislations: The challenges with current laws is they are opaque, complex and there is a huge translation gap between law-making, law-implementing and law-interpreting organizations.

a. Can AI enable us to link a complete chain right from the parent Act to the subordinate Legislations and the amendment notifications?

b. Can it also help lawmakers identify gaps and redundant laws?

c. Can it inform an entrepreneur if he/she wants to open a manufacturing unit in the State of Maharashtra and what acts and compliances apply to it?

In summary, AI provides a digital neural layer that connects the citizen-facing nerves (DPI touchpoints) to the brain and organs (government back-end systems). It ensures that data flows smoothly, work moves swiftly, and decisions are informed and consistent.

Part 2 will focus on the deployment approaches, types of policies and standards we need, procurement of those systems, evaluations and safe and ethical use.

I like the framework you’re setting up here! The idea of AI as a “layer” in the infrastructure is a helpful one. I think the key question for each of those use cases you’ve outlined is how much error we’re willing to accept. If citizen comments are summarized lossily, maybe that’s okay, but if business regulations are summarized lossily to an entrepreneur, as in your example, maybe that is less okay. Of course human run systems are prone to errors too, but introducing AI creates some interesting questions about who is liable if things are incorrect. If the AI says you need the wrong forms but you fill the forms it requests, do you get access to a welfare program? Looking forward to Part 2!